“The conch exploded into a thousand white fragments and ceased to exist” – William Golding

– A Research Article, written by Deseree Arzu – The Queen conch is a well-loved delicacy; an important part of Belizean culture that has been around for generations. So, for many Belizeans, Golding’s quote above is not something they imagine or think about happening, particularly in a small country of 360,000 inhabitants; especially since the symbolism of the quote refers to the destruction of a people’s way of life.

But, we need not look very far to the Caribbean nations of the Bahamas and Jamaica; or our Latin American neighbors in Mexico, to realize that it’s not a far-fetched reality, despite conch fishery in Belize being small-scale. This means that there are only approximately 2,600 registered fishers who use small fishing vessels and boats to catch conch and other seafood. The Bahamas, Jamaica, and Mexico have all, at some point, instituted moratoriums in order to address a serious shortage of what Bahamians refer to as “royalty”, and Mexicans call Caracol Rosado; i.e. the Queen conch.

As a matter of fact, in Jamaica, there remains a ban on conch fishing until January 2020; while the Bahamas, experts recently announced that conch stock could be depleted within the next ten years. Could Belize be facing the same situation as its Caribbean and Latin American neighbors? The question is relevant, especially since fishers, cooperatives, restaurateurs, and NGO’s have conflicting views about whether there is a decline of the species. Many attributes any imminent threat to the industry to alleged illegal fishing by our Central American neighbors; and the lack of adequate enforcement by local authorities. In addition of excessive fishing activities, Dirk Zeller et. al, in the Main Fisheries Atlas (2002) attributes the threat to Belize’s conch and overall fisheries to coastal development and the ‘difficult relations with Guatemala and Honduras’.

Although Belize and Guatemala signed a Special Agreement in 2008 to address the territorial dispute, at the behest of the Organization of American States, it has done little to quell tensions, particularly at Guatemala’s western border with Belize where there have been several reported incidents of illegal border crossings, poaching, fatal shootings, and maritime issues, including reports of illegal fishing. Additionally, a number of Guatemalan fishers have valid licenses to fish in Belize waters, which many Belizean fishers have since protested. Belize’s Minister of Fisheries, Dr. Omar Figueroa has said that those licenses will not be renewed when they expire. And, although the tensions between Belize and Honduras are not at the level it has been with Guatemala, there have also been reports of Honduran fishers illegally selling Belizean seafood products in that country, which may be one the reasons for the reported over-fishing in Belize.

Pic 1: Sarteneja fishers with conch catch at Fishing Area #8, Glover’s Reef (J. Maaz); Pic 2: Conch diver holding onto small vessel at Glover’s Reef (A. Tewfik)

In 2018, Belize exported 882, 950 pounds of conch to the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada; accounting for approximately BZD $13,097,220 in export earnings. In the United States, which once imported over 1,000 metric tons of conch from the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, and Belize, conch harvesting has been banned for over three decades; and Honduras, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic, who once exported to the U.S., have all banned all exports of conch. As a matter of fact, Honduras has limited its export of conch to a “scientific” quota; meaning that conch can only be harvested for scientific surveys; but the quota is restricted to 210 tonnes annually. Due to a decline in exports 15 years ago, that country suspended commercial fishery, and disallowed domestic consumption.

Here in Belize, tourists travel thousands of miles to enjoy our seafood; and local residents enjoy conch soup, (popularized in song locally, by Punta Rock star Chico Ramos and Sounds Incorporated Band; and later regionally by Honduras’ La Banda Blanca); conch fritters, stewed conch, fried conch; and conch ceviche (made with tomatoes, onions, cilantro, lime, salt and pepper). All these delicacies are affordable for both locals and visitors; ranging from US $0.50 per conch fritter, to US $5.00 to $7.50 for conch soup. A pound of conch locally cost about US $6.00. The livelihoods of fishers, restauranteurs, middlemen, the fishing cooperatives, and Belize’s overall economy, particularly tourism, depend largely on seafood, and in particular conch fishery.

Conch ceviche being served at El Fogon Restaurant, San Pedro

Amy Knox, owner and manager of Wild Mango’s Restaurant, a Fish Right Eat Right establishment on San Pedro, Ambergris Caye, Belize, stopped serving conch and lobster 12 years ago. Knox explained that “I was actually seeing the populations physically decrease; and with talking to fisherfolk, they now were having to go all the way to Turneffe to get proper-sized conch no longer in our backyard.” In the beginning, customers became angry when Knox informed them that she had no conch or lobster; some of them even left the restaurant; but as time went on, they understood and remained regular customers.

In Belize, Queen conch is managed using a minimum shell length size of 7 inches, and a minimum clean meat (without the shell) weight of 3 ounces. The season closes each year from July 1 to September 30, or whenever the annual fishing quota is reached. However, despite attempts to manage the queen conch fisheries, the species continues to be listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The Queen conch’s slow growth and inclination to congregate in shallow waters make them susceptible to over-exploitation. So, it is important that we protect it for future generations, as mandated by the country’s Fisheries Department. But are we doing that? And what exactly does ‘protection’ entail?

According to Belize’s Fisheries Administrator, Beverly Wade, the Queen conch fishery is “the second most important and probably the best-managed fishery in Belize … and the region”; the first being lobster. Wade explains that Belize has made significant advances in the Management Regime for conch at national, regional and international levels. Having been listed under Appendix II of CITES, Wade states that “much of the national initiatives have focused on data collection, monitoring and research to ensure the sustainable use of this resource”. Despite the efforts though, scientific studies are showing that juvenile conch species are being over-harvested, and there is a need to implement a different approach to determining maturity; i.e. instead of using the tradition shell length, lip thickness should also be used.

A recent peer-reviewed, published Queen Conch Research, conducted by WCS marine scientist, Dr. Alexander Tewfik, et. al, which looked specifically at Glover’s Reef Marine Reserve (GRMR) over a 15-year period, makes several conclusions, including that:

1. Shell length or meat mass alone are NOT suitable proxy for determining maturity and should not be used to select individuals for harvest because adult conch at the reserve are those with shell lip thickness of 0.4 inches or greater and meat mass greater than 6 2/4 ounces.

2. The use of inappropriate minimum size limits (7 inches; 3 ounces’ market clean meat mass) over the last 4 decades has allowed significant juvenile harvest, threatening the maintenance of spawning stock.

3. The fishery appears to have truncated the shell-length size distribution of conch with a flared shell lip (i.e. sub-adults < 4 inches, adults > 4 inches) over the last 15 years at GRMR by always selecting the largest/fastest growing.

The researchers found that the reduced shell length observed in lipped conchs (all with lips > 0.04 inches) may lead to a “significant impact on the reproductive success of the population as well as diminished economic yield”. This is due to the harvesting of juveniles since adults have much more meat per animal but are in low density. In essence, “adult fecundity is linked to age and shell size/volume – more space for bigger gonads,” says the Research.

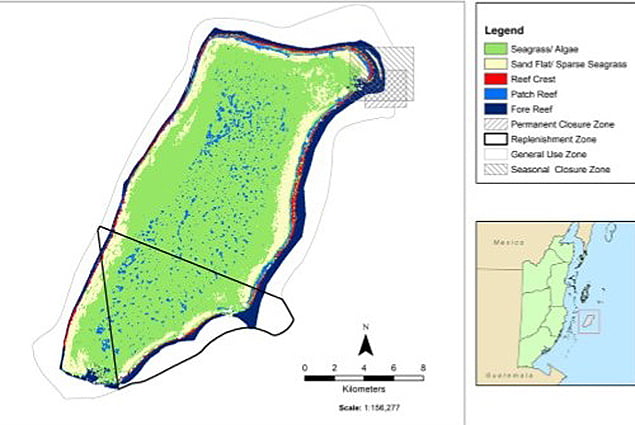

Glover’s Atoll (Marine Reserve) habitats and management zones. The reef crest forms almost a complete barrier around the lagoon, with exception of three main channels. The outer boundary (200-meter depth contour) encloses 350 km2, while the boundary (30m depth contour) of the coloured areas is approximately 262 km2. Inset: The position of Glover’s Atoll on the coast of Belize. Permanent and seasonal (1 December to 31 march of the following year) closure areas are designated specifically for the protection of a Nassau grouper aggregation site but do pertain to all fishing activity. (Picture courtesy Tewfik, et. al 2018)

A Study by James Foley, and Miwa Takahashi of the Toledo Institute for Development and Education (TIDE), which conducts conch studies in the Port Honduras Marine Reserve, located approximately 100 miles south of Glover’s, shows similar trends. That research concludes that there is an “urgent need to base size-limits on lip thickness not shell length”. Valdemar Andrade, Executive Director at the Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association, which supports conch research at Turneffe Atoll, makes a similar observation, based on data collected between 2016 and 2018. However, Andrade explained that “As a scientific approach … it is fine to utilize lip thickness for research purposes and targeted catch data, but as an enforcement tool, it would be difficult since fishers do not deliver landed conch in shell”.

Meanwhile, Amanda Burgos-Acosta, the Executive Director at the Belize Audubon Society, which does conch research work at Lighthouse Reef Atoll, says “Studies at Lighthouse Reef Atoll are showing that there are more juveniles than adults”, even though data shows a reduction in harvesting. This could be due to several factors, including weather and early season closer for conch”. Further studies would be needed to confirm this.

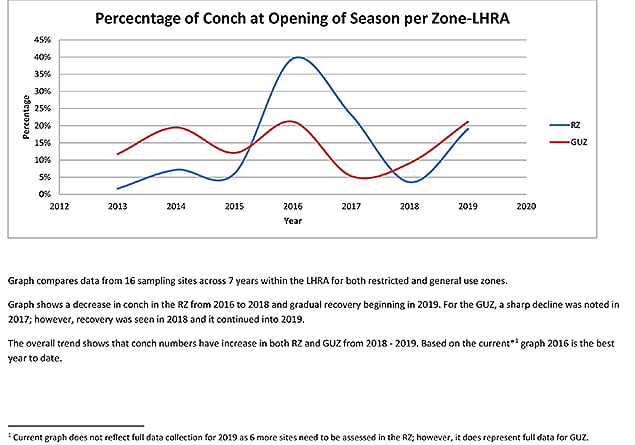

Graph shows data, based on studies conducted at Lighthouse Reef Atoll (Belize Audubon Society)

The lead researcher for the Glover’s study, Dr. Alexander Tewfik, recommends amendment to Belize’s conch fishery legislation, to include “refinement of the individual size‐based regulations … to lip-thickness, and associated increase in meat mass”. This, he says will enable preservation of spawning stock, “recruitment and local recovery as well as regional harmonization of regulations”. Importantly, the new Fisheries Amendment Bill makes provision in Section 11 (1) for the Minister, on recommendation of the Fisheries Administrator to ‘declare by Order … that a specific area, fishery, stock, or species of fish be closed to fishing in order to (a) prevent further depletion; (b) promote recovery and ecosystem services; and (c) protect critical habitats”.

But, apart from legal provision, how realistic, or feasible is the recommendation to use lip thickness for determining maturity, particularly for fishers who fully recognize that ‘time is money’; and having to use callipers to measure lip thickness would be time-consuming, and will ultimately affect their livelihoods?

Belizean-American, Aaron Anderson, has a different suggestion. He is eager to reintroduce conch-farming to the country upon his return to Belize. There was an attempt to do so many years ago on San Pedro, Ambergris Caye, Belize. Research is showing that there is only one known conch farm in the world. It is located in Turks and Caicos. But, from all accounts, it’s a very expensive venture to undertake, one that requires considerable financial investment. Meanwhile, Shane Young, of BAS, believes that introducing lip thickness as a method to measure maturity of conch “will reduce significantly the catch per unit effort (CPU) of the fishers” because it will take more time to measure lip thickness.

But the fishers of the Hopkins Fisher Association disagree. President, Mr. Norman Castillo, popularly known as Strings, says his Association would support any recommendation that would help to sustain the seafood industry, including the use of callipers if necessary. Castillo categorically stated that “My fishers know that we don’t encourage or support anyone who fishes under-sized products. If a new legislation is implemented which mandates we use lip thickness to measure maturity, then we’ll do what we have to do to help sustain this industry”. To the contrary, Leonardo Awayo, a fisher from Copperbank Village in Corozal, who has been fishing for over 23 years, says categorically that “if something like that is implemented, fishers will not be able to get the amount of conch they are getting now, and the Coops will not be able to get the quota they require”. Awayo recommends setting quotas for fishers.

However, Chairman of the National Fishermen Producers Cooperative Society Limited, Elmer Rodriguez, who is the Fisher of the Year 2019, says consultation with fishers is important in order to create awareness of what is happening with conch. While Rodriguez agrees that there is a need to ensure that the fishing industry remains viable and sustainable, he expressed that if legislation is passed mandating use of lip thickness to measure maturity, “it will certainly affect the landing of conch.” He explains that there is only a small percentage of conch that would conform to the new rule since “the majority of conch that is fished are juveniles. It will affect our economy because the Cooperative will not be able to export the number of conch they currently export to the foreign market”. These markets include the United States, Mexico, United Kingdom, European Union, Central America, CARICOM, Canada, Netherland Antilles, and China. According to data from the Statistical Institute of Belize, exported conch in 2018 accounted for 882.95 thousand pounds representing $13.097m in foreign earnings.

In reference to the recommendation that suggests the use of lip thickness to determine maturity, Fisheries Administrator Wade says that to date “no such requirement for institution of lip thickness has ever been made by any fishery management organization” neither in the Caribbean or Central American region. She added that at a recent meeting of the Western Central Atlantic Fishery Commission, held in Miami, Florida in July 2019, members did not recommend any management measures for Queen conch based on lip thickness. This is confirmed in the Food and Agriculture’s Regional Queen Conch Fisheries Management Plan, which calls for regional coordination to ‘avoid duplication in the efforts and to achieve the sustainable management of this transboundary fishery resource in the region’.

Corozal fisher in his boat cleaning conch while at Glover’s Reef (V. Burns-Perez)

Then, there are some Belizean residents, some of whom preferred to remain anonymous, who are dismayed that the Coops are more concerned about meeting their quotas and exportation of conch, rather than implementing rules and regulations that would help to protect the industry and livelihoods in the long term. However, one fisher recommended landing of whole conch (with shell); and instituting a 5-year moratorium in order to replenish stock. Some Belize City fishers like Dave Fairweather don’t think this approach will work. Recently presented with the Oceans Hero Award, Dave says that an effort must be made to properly inform and educate fishers. He noted that “fishers like us have been practicing sustainable fishing. We don’t fish under-sized conch; but there are fishers who do”.

But, is there a one-step approach to addressing any concerns regarding within the conch industry? Milton Haughton, Executive Director of the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism, says no! Haughton believes that it will take a multi-faceted approach to address the shortage and over-harvesting of conch in Belize. Ms. Wade agrees with Mr. Haughton. She explains that “The Management of the Queen Conch Fishery is multi-dimensional and the effectiveness of such a management regime has to take several factors into consideration”. These factors are:

1. The Queen Conch that is legally harvested in the shallow fishing areas of Belize are not considered adult and spawning individuals that have developed thick flared lips but rather sub-adult individuals.

2. In Belize, Queen Conch fishing is restricted to a certain depth (75 ft maximum) where divers can reach by free diving only.

3. Countries like Honduras and Nicaragua harvest adult and spawning individuals because SCUBA gear is still allowed for commercial fishing (the use of SCUBA gear for commercial fishing is prohibited in Belize since 1977).

4. The Fisheries Department is also guided by the regional and CITES recommendations for the management of Queen Conch to ensure that its regime is in concert with the expert advice for the long-term sustainability and effective management of the species.

Mr. Haughton agrees that trying to manage conch fishery is a challenge that requires adequate policy frameworks be put in place. Therefore, it is important “to ensure that in going forward, and in seeking to optimize benefits and value from the fishery you do not leave out the small-scale fishers”.

The conflicting views regarding the decline of conch and some reservations towards recommendations to use lip thickness to determine maturity may be an indication of the need to have further discussion on the subject. It would also be worthwhile to have additional long-term conch studies in other Marine Protected Areas, especially since Belize’s Barrier Reef System is an important part of the Mesoamerican Reef -that encompasses Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. It is also a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site, important not only for the aesthetic value it provides to visitors and residents of Belize, but also for tourism, recreation, livelihoods, and our overall blue economy. While climate change remains a threat to our environment, it is human activity that remains the greatest threat to protection of the Mesoamerican Reef.

The truth is, though, there are some things we can all do to help protect Belize’s conch industry. Firstly, we can stay informed about any developments within the fishing industry by reading more. Secondly, we must not buy undersized or underweight conch. Thirdly, we must purchase conch only during the open season. And lastly, we must report any illegal activities whether on land or at sea. Anyone can report illegal activities, anonymously, using the CRIME STOPPERS number at 0-800-922-TIPS.

The authors of the Glover’s study say that at the very minimum to help sustain the conch fishery, there is need for effective patrol of replenishment zones (no-take zones), which could serve as a measure to control access to Queen conch, particularly in shallow waters of up to 30 meters. Additionally, they say it would help if the Draft Fisheries Amendment Bill, which allows for specific management plans for conch, is passed in Belize’s House of Representatives.

It is vital that we continue to put in place measures to address the decline of Queen conch and enforce those measures that are already in place. It is only through swift and continuous action that we will help to save the conch industry, and subsequently the Mesoamerican Reef, from threat or a fate similar to our Caribbean and Latin American neighbors.

NOTE: This Reporter reached out to the Minister of State in the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Forestry, the Environment, Sustainable Development, and Climate Change, Honourable Dr. Omar Figueroa to record an official government position on the research, but we did not receive a response to our questions. We hope to conduct follow-up stories on this topic, in the future.

“This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.”